The HSC Science subjects were changed dramatically in 2018, with the new depth studies forming a huge part of the new syllabus. These unique tasks give students control over what they learn and how they choose to present it. As depth studies mimic the style of learning in university, they require students to apply the academic skills of research and referencing, skills which are often overlooked or not taught fully in class.

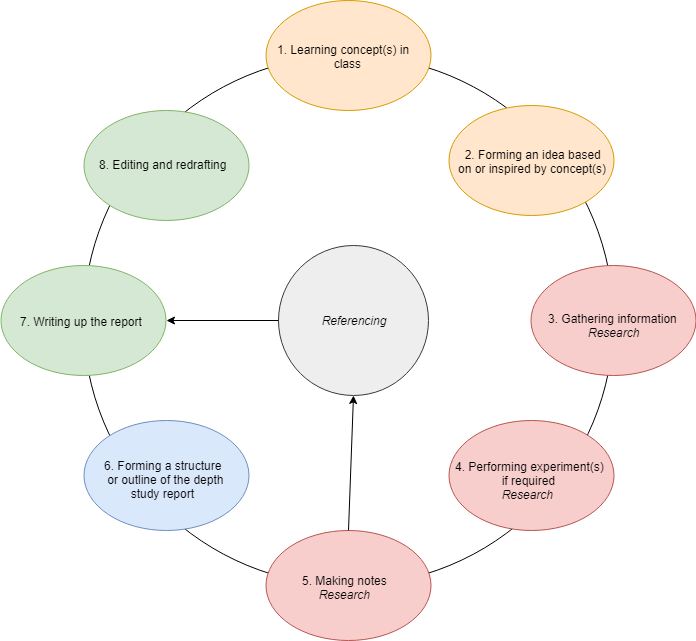

The process of writing a depth study can seem daunting; lets break it down into smaller steps so we can see where research and referencing fit in.

Research

Research is simply the act of gathering information from sources to reach conclusions. It includes collecting information from both your own experiments and from the various sources you find.

So, you’ve paid attention in class, (hopefully) been inspired and found a topic. But you might find yourself asking the questions: How do I start my depth study? Where do I look for information?

Although this situation is common, it is easy to overcome. Follow these general tips below to get started on your research:

- Scan. Start looking at sources containing a broad range of information to gain a better understanding of your topic. These may include textbooks, websites and encyclopedias (such as Wikipedia or Britannica). While online is a great place to look, also check with a librarian at your local library to gain a wide range of sources.

- Search. Online databases are collections of scholarly papers, and they’re your best bet at finding specific information for your depth study. Search through databases such as Google Scholar, which are free and easily accessible online. Boolean Operators are tools which will help you narrow down your results.

- Evaluate. With the variety of available sources online, it can be hard to determine which ones are suitable for your research. One effective method of evaluating sources is by using the CRAAP method. This method involves checking:

- Currency (Is the information found the most recent? Does this impact the reliability of the source?)

- Relevance (Does the information contribute towards your topic and aim? Is the information too complex/simple for your purpose?)

- Authority (Has the source been composed by qualified authors?)

- Accuracy (Quite simply, is the information accurate?)

- Purpose (Are there any biases in your source?)

See here for more detail on the above 5 points.

If you are also required to include an evaluation of your sources for your depth study, use the above 5 points as a framework for this section.

- Make notes. Highlight, annotate and make notes as you go through your sources. It may also be useful to save online sources in a bookmarks bar

Referencing

Meanwhile, referencing is a method of acknowledging the sources you draw information from. Whenever you paraphrase, summarise or quote someone else’s work, you must acknowledge them twice: in the body (in-text citation) and at the end of your report (reference list).

The following sentence is an example of a journal article reference in the APA 6th style (see end of post for the reference list entry). A national survey found that 84% of junior doctors slept less than 7 hours per night, which is lower than the recommended 7-9 hours (Markwell & Wainer, 2009).

Referencing is important because it:

- Acknowledges and gives credit to the work of other writers/researchers

- Provides evidence for the assertions you make which

- Makes your writing more credible and persuasive

- Lastly (and likely most importantly) avoids plagiarism!

As there are numerous ways to cite, make sure you check with your school teachers/examiners on their preferred referencing styles and methods. If you don’t have access to programs such as EndNote which automatically reference for you, referencing is a skill which can easily be learnt: this website contains guides for the most popular referencing styles.

Markwell, A. L., & Wainer, Z. (2009). The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: insights from a national survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 191(8), 441-444.